The folks at the Impossible Project, the Berlin-based company that manufactures and sells integral film for Polaroid cameras, released their latest iteration of film for 600-type cameras in March of this year: Gen 2.0 B&W film. It’s the first film unveiled by Impossible since Stephen Herchen, a former vice president of Research and Development and Chief Technology Officer for Polaroid Corporation as well as a co-founder of ZINK Imaging, joined Impossible as CTO in late 2013. They’re calling the Gen 2.0 film “our first truly instant product.” The company says the film renders an image in 20-25 seconds and unlike other Impossible films, it doesn’t require shielding from light during early development.

[vimeo https://vimeo.com/123926428 w=1440&h=600]I’ve had an ongoing love/hate relationship with Impossible films since 2009, starting with their Artistic AZ film. I’ve pulled my hair out trying to make well-exposed images with Impossible films. And no matter how many hoops I’d jump through, no matter how much I wanted the film to work, the experience almost always left me with an “emperor has no clothes” feeling. Compounding my frustrations, Impossible offerings like their Round-frame and Lulu Guinness-frame films struck me as mere marketing ploys, akin to Polaroid’s Taz-Cam efforts when the company was in decline. Frankly, I felt Impossible had regressed and was catering to a less discriminating demographic. So I stopped buying their films. My last Impossible purchase was in June 2014 (in spite of my boycott, Impossible sold 23 million units of their film last year).

This spring, the company followed-up their “Gen 2.0” announcement with an #askthefactory Twitter chat with Herchen. And I ran across a review of the film by Patrick Clarke. The chat and review were incentive enough for me to give Impossible another shot. So in April I bought a pack of their latest film, hoping that they’d made some improvements in their product but (given our volatile history) keeping my expectations in check.

I shot the film as if it were a pack of Polaroid 600 film, using a SLR 680, no shielding of the image as it ejected, or using a neutral density filter to control exposure. I did, however, follow Impossible’s suggestion to turn the exposure wheel a tad to lighten.

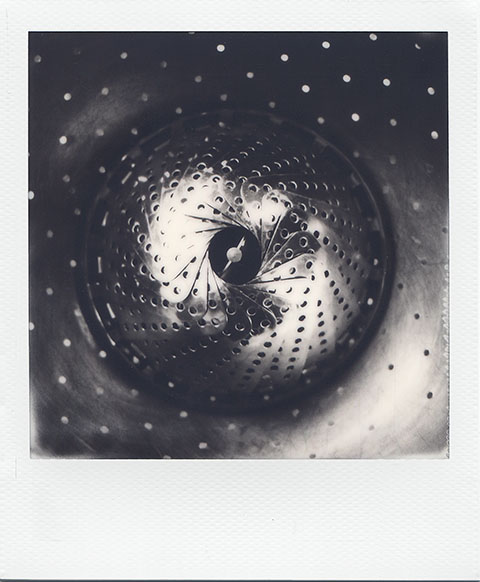

The film performed admirably, rendering a beautiful range of tones and a fully developed image in about twenty minutes. Its shortcoming is that, well, it’s short-lived. Like other Impossible BW films, those wondrous B&W tones shift to sepia rather quickly. I’ve found there’s about 36-hour window to get the image scanned before it begins to degrade.

Will I ever buy another pack of Impossible film? Yeah, but it’s more a question of when. I think it’s fair to say Impossible has turned a corner in terms of what the company’s then-CEO (now Chairman) Creed O’Hanlon called “instantaneity” in a 2014 open letter to customers. Making a picture with this new film is simpler and easier and faster than it has been with other Impossible films. But the stability and longevity that’s a hallmark of Edwin Land’s Polaroid films–and the gold-standard for instant film–still eludes the grasp of the Impossible Project.